The Story Of The Lone Wolf And His Son

- Noble D. LeMoore

- Sep 25, 2025

- 16 min read

Updated: Nov 20, 2025

This painting, which I titled “The Lone Wolf And His Son,” Finds its origin in the creative minds and pens of writer Kazuo Koike (1936-2019) and illustrator Goseki Kojima (1928-2000). The Original Manga series Kozure Ōkami [子連れ狼] is translated as “Lone Wolf and Cub”. It first appeared in a weekly publication series on Weekly Manga Action [週刊漫画アクション] between 10 September 1970 and 1 April 1976. It is a seinen-type magazine targeting an adult audience, in contrast to Shōnen magazines for younger audiences. In fact, the Kozure Ōkami series contains graphic violence and sexual scenes not suitable for a younger audience. However, this Manga is deeply anchored in Japanese culture just by the details and historical accuracy of feudal Japan of the Edo [Tokugawa] period (1603-1868). It is also a great portrait of the philosophy and value systems of the Samurai Bushido code. Notably, the crest, mon [紋] or monshō [紋章], that we can see in the movie and at the ending credits, is the official family emblem of the Tokugawa clan *Tokugawa-shi, Tokugawa-uji [徳川氏].

The original publisher is Futubasha in Japan, and the English translation is under the banner of Dark Horse Comics. *The English translation started in the year 2000, and the completion of the 28-volume series finds its rest in the first publication in December 2002.

Of the original manga, a total of 145 Chapters were published each week in the Shōnen Magazine. They were later compiled as 28 standalone volumes known as tankōbon [単行本].

This painting, which I titled “The Lone Wolf And His Son,” Finds its origin in the creative minds and pens of writer Kazuo Koike (1936-2019) and illustrator Goseki Kojima (1928-2000). The Original Manga series Kozure Ōkami [子連れ狼] is translated as “Lone Wolf and Cub”. It first appeared in a weekly publication series on Weekly Manga Action [週刊漫画アクション] between 10 September 1970 and 1 April 1976. It is a seinen-type magazine targeting an adult audience, in contrast to Shōnen magazines for younger audiences. In fact, the Kozure Ōkami series contains graphic violence and sexual scenes not suitable for a younger audience. However, this Manga is deeply anchored in Japanese culture just by the details and historical accuracy of feudal Japan of the Edo [Tokugawa] period (1603-1868). It is also a great portrait of the philosophy and value systems of the Samurai Bushido code. Notably, the crest, mon [紋] or monshō [紋章], that we can see in the movie and at the ending credits, is the official family emblem of the Tokugawa clan *Tokugawa-shi, Tokugawa-uji [徳川氏].

1. The Assassin's Road | 8. Chains of Death | 15. Brothers of the Grass | 22. Heaven & Earth

|

2. The Gateless Barrier | 9. Echo of the Assassin | 16. Gateway Into Winter | 23. Tears of Ice |

3. The Flute of the Fallen Tiger | 10. Hostage Child

| 17. The Will of the Fang | 24. In These Small Hands |

4. The Bell Warden | 11. Talisman of Hades | 18. Twilight of the Kurokuwa | 25. Perhaps in Death

|

5. Black Wind | 12. Shattered Stones | 19. The Moon In Our Hearts | 26. Struggle in the Dark |

6. Lanterns For the Dead | 13. Moon in the East, Sun in the West | 20. A Taste of Poison

| 27. Battle's Eve

|

7. Cloud Dragon, Wind Tiger | 14. Day of the Demons | 21. Fragrance of Death | 28. The Lotus Throne

|

Kazuo Koike

Goseki Kojima

Lone Wolf and Cub - Dark Horse Comics English translation

This Manga series gave birth to the film series on Nippon TV, mainly directed by Kenji Misumi (1921-1975) and starring Tomisaburô Wakayama (1929-1992) as Lone Wolf [Ogami Ittō] and Akihiro Tomikawa (1968) as his son [Ogami Daigorō]. Kenji Misumi’s film series was televised between 1972 and 1974. Two other directors, Buichi Saitô (1925-2011) and Yoshiyuki Kuroda (1928-2015), contributed to the series, keeping its pace and integrity. The first three (3) series were produced by Wakayama’s brother, Shintaro Kastu (1931-1997); and the last three (3) by Tomisaburô Wakayama himself.

Here are the titles of the series:

- 1) Lone Wolf and Cub: Sword of Vengeance released on 15 January 1972 The Original title is Kozure Ôkami: Ko o kashi ude kashi tsukamatsuru [子連れ狼 子を貸し腕貸しつかまつる]. Directed by Kenji Misumi.

- 2) Lone Wolf and Cub: Baby Cart at the River Styx, televised on 27 April 1972. The Original title is Kozure Ôkami: Sanzu no kawa no ubaguruma [子連れ狼 三途の川の乳母車]. Directed by Kenji Misumi.

- 3) Lone Wolf and Cub: Baby Cart to Hades, televised on 2 September 1972. The Original title is Kozure Ôkami: Shinikaze ni mukau ubaguruma [子連れ狼 死に風に向う乳母車] directed by Kenji Misumi.

- 4) Lone Wolf and Cub: Baby Cart in Peril was televised in 30 December 1972. The Original title is Lone Wolf and Cub: Baby Cart in Peril is Kozure Ōkami: Oya no kokoro ko no Kokoro [子連れ狼 親の心子の心] directed by Buichi Saitô.

- 5) Lone Wolf and Cub: Baby Cart in the Land of Demons, televised on 11 August 1973. The original Japanese title for the 1973 movie Lone Wolf and Cub: Baby Cart in the Land of Demons is Kozure Ōkami: Meifu Madō [子連れ狼 冥府魔道] directed by Kenji Misumi.

- 6) Lone Wolf and Cub: White Heaven in Hell, televised on 24 April 1974. The Original title is Kozure Ōkami: Jigoku e ikuzo! Daigoro [子連れ狼 地獄へ行くぞ! 大五郎] Directed by Yoshiyuki Kuroda.

The first two episodes gave birth to the American adaptation titled “Shogun Assassins”. The title itself was inspired by the 1980s NBC miniseries “Shogun” directed by Jerry London and starring Richard Chamberlain, Toshirô Mifune, and Yôko Shimada. Robert Houston and David Weisman strategically chose the title “Shogun Assassin” to capitalize on the commercial success of the NBC miniseries in the United States. “Shogun Assassin” is an edited version of the first episode, “Lone Wolf and Cub: Sword of Vengeance,” and the second episode, “Lone Wolf and Cub: Baby Cart at the River Styx”. Including the ending credits, the movie runs 85 minutes. Eleven (11) minutes of footage is taken from the first episode, and the main part is approximately 70 minutes of footage from the second episode. David Weisman as Producer, Robert Houston as Director, and Lee Percy as Editor. Shintaro Kastu and Hisaharu Matsubara also hold credits as producers on the American version. Kazuo Koike, with Robert Houston and David Weisman, gets the credit for the screenplay. This version is presented to the American audience through the Toho company/Katsu Productions.

Robert Houston

David Weisman

The 1980s NBC Miniseries “Shogun”, directed by Jerry London, is adapted from

James Clavell’s Novel published in 1975

One noticeable thing to observe is that the stories of the original TV series differ from the movie “Shogun Assassin”. The said Shogun in the movie is not the one in the TV series. In “Shogun Assassin,” the Shogun is portrayed as a ruthless psychopath who rules Japan with an Iron fist. As Daigoro narrates: “People said his brain was affected by devils.” In the original TV series “Lone Wolf and Cub”, the Shogun is more of a neutral, concealed figure that we briefly see, yet he has a distant presence on the story. The man who is presented as the mad Shogun in the American movie version looks like an old man with a white beard. This man is in the original TV series Retsudo, the head of the infamous Shadow Yagyu Clan, who conspires for the downfall of Ogami Itto from his position of Shogunate Executioner.

The American story really begins when the original series of “The Lone Wolf And Cub” are aired in Little Tokyo in Los Angeles during the mid-1970s. This is where David Weisman and Robert Houston saw the first two episodes of the series. With money loaned by friends, they were able to get the rights for “Lone Wolf and Cub: Sword of Vengeance” and Lone Wolf and Cub: Baby Cart at the River Styx. It is said to have been a 6-month labor of studio editing. The finished product was sold to be distributed through Roger Corman’s company, New World Pictures, to be then broadcast through the Grindhouse circuit in 1980. It was later mastered for video cassette by MCA/Universal Home Video.

While Jim Evans was the visual artist who did the poster for the movie, the Daigorō narration voice was dubbed by the young voice of his son, Gibran Evans. Ogami Ittō was dubbed by Actor/Director Ernest Lamont Johnson Jr (1922-2010). Comedian/Actress Sandra Bernhard did the voice of the “Supreme Ninja,” originally played by Japanese actress Kayo Matsuo.

The IMDb Anecdotes tell that in the early 1980s, the movie was banned in the UK due to the “video nasty” bad press. The Video Recordings Act of 1984 has put the retailers under the obligation of carrying an official rating. All this led to police raids, seizing copies from video rental shops. The distributors were not motivated to apply for a certification following the Act legislation. Therefore, the movie did not boom as it would have, even though the new distributor, VIPCO, owned the rights at the beginning of the 1990s.

I have a promotional version of the movie soundtrack released by Baby-cat Productions. It is a limited Pressing edition. The Shogun Assassin Original Motion Picture Soundtrack is produced by Mark Lindsay. Lindsay is also part of the music composition in collaboration with W. Michael Lewis and Robert Houston. I Am not sure whether they sampled or replayed some sounds; however, they also used some material from the original musical theme. The music is performed by The Wonderland Philharmonic. “Wonderland” is said to refer to a house that Lindsay once lived in. The soloists are W. Michael Lewis, Mark Lindsay, Mark Singer, Lanie Cook, and Robert Houston. Recorded and mixed at Icons Studios, Hollywood.

This is where my journey begins. I may have heard the intro of the movie with Daigoro’s voice when I was younger, yet it is all blurry. I can certainly say that when I heard Gza’s Liquid Sword intro, it was a déjà vu moment, or shall I say déjà entendu. Rza is the one who had the idea to add extracts of the movie at different parts of the album. We can hear samples from the movie in the following songs:

1)The Beginning of “Liquid Sword”

2) The beginning of “Dual Of The Iron Mic” a)

5) The beginning of “Cold World”

7) The beginning of “4th Chamber”

12) the end of the song “I Gotcha’ Back”.

a) The song: ”Dual of the Iron Mic” also contains an extract from the movie "The Dragon, the Hero" (1979). Directed by Godfrey Ho.

Liquid Sword is a classic of the Wu-Tang legacy that carved a sharp sound, lyrical sword plays, street smart, and philosophy that leaves a solid foundation, and serves as a reference of our Hip-hop era for generations to come. The fact is that Gza’s album brought me to the original soundtrack, the music brought me to the movie, and the movie brought me to the Mangas. However, when it comes to Mangas, I Am really a novice. I do have a nephew who is really into it, who can give me some cues. Now, when I have an obsession, I want to get to the heart of it. I did this painting for its cultural significance in hip-hop, martial arts, Nippon culture, cinema, literature, and visual art.

GZA – Liquid Swords

Shogun Assassins (Main Theme Song) 1980

Another great reference is the Movie Kill Bill Volume 2. Directed by Quentin Tarantino, starring Uma Thurman, David Carradine, and Michael Madsen. There is a scene with “The Bride” Beatrix Kiddo, played by Uma Thurman, and her daughter B.B. Kiddo, played by Perla Haney-Jardine. They are lying in a bed watching the movie “Shogun Assassin”, and we can hear the narrating voice of Daigoro at the beginning of the film. Tarantino possibly wanted to create a contrast by portraying “The Bride” (Beatrix Kiddo) and B.B. Kiddo as “The Wolf and Her Daughter”.

Kill Bill Vol. 2: Daughter About Her Scene

Other TV series inspired by the original Manga were broadcast:

1) The jidaigeki [時代劇)] The television series Lone Wolf and Cub was also directed by Kenji Misumi and broadcast by Nippon TV between 1973 and 1976. This 3-season series was produced in a traditional drama format with its unique storytelling approach. Kinnosuke Yorozuya played the role of Ogami Ittō, and Katzutaka Nishikawa played the role of Ogami Daigorō for the first two seasons and the third season by Takumi Satô.

2) Kinnosuke Yorozuya plays the role of Ogami Ittō once more in 1984 on the TV movie titled Kozure Ōkami: Jigoku e ikuzo! Daigoro [子連れ狼 地獄へ行くぞ! 大五郎] "Lone Wolf and Cub: An Assassin on the Road to Hell" also known as Baby Cart in Purgatory. The TV movie is a sequel to the previous series.

3) Lone Wolf and Cub, directed by Kôjirô Fujioka, and originally broadcast by TV Asahi between 2002 and 2004. Kin'ya Kitaōji played the role of Ogami Ittō, and Tsubasa Kobayashi played the role of Daigoro. The series is slightly altered as the character of Tanomo Abe is discarded from it. The seasons can be found on the OTAKU YouTube page.

Footage of historical monuments can be seen in both the original TV series and “Shogun Assassin”. There is to shots of the Castle during the movie in the first 37 seconds and at 8:37 minutes. The Himeji Castle Himeji-jō [姫路城] is a substitute for the Edo Castle, which is the home of the Shogunate during the Tokugawa Era. The Himeji Castle was alternatively chosen because of its size and pristine condition. The Himeji Castle is more appealing aesthetically, while the Edo Castle lost its large central tower. The Castle was also screened in movies such as “Ran” directed by Akira Kurosawa and “The Last Samurai” directed by Edward Zwick. The Himeji Castle is the most visited in Japan.

Himeji Castle is situated in Himeji in Hyōgo Prefecture – Japan

There is a scene in the movie where Daigorō is taking care of his father, who is exhausted and injured. Daigorō finds himself in front of a statue made of stone. At the feet of the statue, there is a loaf of bread that Daigorō trades with his Jacket. It is the statue of a divinity named Jizō [地蔵], also known as Dizang [地藏] in China, Jijang [지장] in Korea, Địa Tạng [地藏] in Vietnam, Sa yi snying po [ས་ཡི་སྙིང་པོ] in Tibet, and Ksitigarbha [क्षितिगर्भ] in India. He is of great significance in the tradition of Japan. Jizō means “Earth Treasury” or “Earth Womb”. He is a Bodhisattva, which means he has reached enlightenment; however, out of compassion, he stays as a guardian in the earth realm to help people reach the light as well. The deity has a vocation to safeguard those with misfortune, the kids, the mothers, the travelers, and the firemen.

Jizō takes the form of a child-monk carrying a pilgrim’s staff called Shakujo with six (6) rings that fingle to warn animals of his approach. The shakujō is associated with Jizō Bosatsu or O-Jizo-sama, carrying it as a symbol of his role as a guide for souls in the afterlife. The shakujo is a wooden pole topped with a metal finial that features several rings. The most common configuration is 6 rings, while others may have four, eight, or twelve. The six rings are most commonly symbolic of the Six Perfections, Sanskrit Pāramitā [पारमिता], the Six Realms of Existence in Buddhist cosmology. Four rings are for the four Noble Truths, a pillar in Buddhism. Eight is for the Eightfold path, which outlines the path to liberation from suffering. Twelve rings may be symbolic of the twelve links of dependent origination, illustrating the cycle of birth and rebirth.

The use of shakujō creates a bond between monks and the community. As monks walk through the villages, the sound of shakujō alerts villagers, encouraging them to come forward with offerings. This fortifies communal bonds and the virtue of generosity among the people.

The shakujō is also tied to martial arts such as Shorinji Kempo, where it is used as a weapon, fusing the spiritual symbolism with practical fighting techniques. These two elements shed light on the union of Buddhist philosophy and Martial Arts.

Jizō also carries the bright Jewel of Dharma truth, whose light banishes fear. He has a gentle smile that represents the purity of the spirit of man. The “Jizō Mizuko,” meaning “Jizō for the Unborn,” are small statues that people place at graveyards or temples to commemorate miscarried or aborted fetuses. In this sense, Jizō comes for their salvation. There is a more detailed iconography that can be studied.

Jizō, known as Kṣitigarbha in India, first appears in the Ksitigarbha Bodhisattva Pūrvapraṇidhāna Sūtra, which is a popular Mahayana Sūtra. In Japan, there is the Sūtra of the Fundamental Vows of Jizō known as the Jizō Bosatsu Hongan Kyō [地藏菩薩本願経 or 地藏本願経]. This Sūtra is one of the most significant texts associated with Jizō and outlines his vows to save all sentient beings, telling stories about his past lives and the miraculous deeds he performs to serve those suffering in hell and other realms.

The Sūtra of Ten Cakras of Ksitigarbha JP.: Daijū Jizō Jūrin Kyō [大乘大集地藏十輪経]. This text focuses on Jizō’s role as a savior during "the age of degenerate law” known as the Mappō period. It unfolds his miraculous powers and various forms, as well as that of a priest and the judge of hell, Emma-ō [閻魔王] or in Sanskrit Yama [यम], the Lord of Death and Justice.

The Sūtra on the Divination of the effect of Good & Evil Actions JP: Sensatsu Zenaku Gyōhō-kyō [占察善悪業報経]. This Sūtra speaks of the consequences of one’s deed and the role of Jizō in guiding souls through the afterlife.

These selected texts hold a vital role in the rise of Jizō worship in Japan, particularly in the Kamakura era JP: Kamakura jidai [鎌倉時代], between 1185 and 1333 onward. Thus, Jizō became a central figure in the spiritual journey of many, taking the form of compassion and the hope of salvation for the dead and suffering beings.

Daigorō in front of the Jizō statue

Jizō statue with the Shakujō

Jizō in Okunoin Cemetery on Kōya-san, the sacred mountain

Finally, let's dive back to the six rings of the Shakujō that Jizōn carries. As I mentioned earlier, they are most commonly symbolic of the Six Perfections, also known as Sanskrit Pāramitā [पारमिता], and the Six Realms of Existence in Buddhist cosmology.

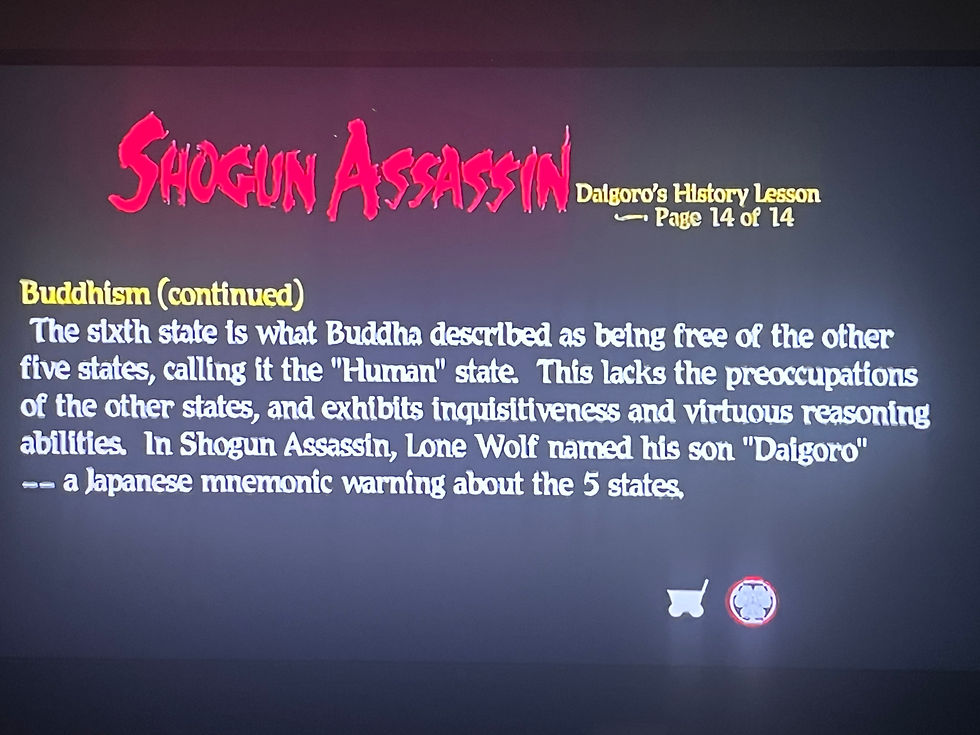

There are many interpretations; however, let's go with what is shown as content on the movie’s Extras titled "Daigoro's History Lesson". The movie's extra interpretation differs from the others by classifying the human state as the transcendental state, while more traditional teachings would say that the Buddha State is the Ultimate One.

“An individual might be preoccupied with:

1. Eternal craving for things – the so-called “hungry ghost” state.

2. Ignorant outlook, not examining theoretical possibilities – the “animal” state.

3. Eternal anger, constantly at war with himself or others – the “hell” state.

4. Overly-competitive, always outdoing others using any means – the “Jealous-god” state.

5. Overly contemptuous with a false sense of having attained a god-like state – the “god-being” state.

6. The sixth state is what Buddha described as being free of the other five states, calling it the “human” state. This one lacks the preoccupations of the other states and exhibits inquisitiveness and virtuous reasoning abilities.

Beings in Hell. Naraka-gati in Sanskrit. Jigokudō 地獄道 in Japanese. The lowest and worst realm, wracked by torture and characterized by aggression.

Hungry Ghosts. Preta-gati in Sanskrit. Gakidō 餓鬼道 in Japanese. The realm of hungry spirits, characterized by great craving and eternal starvation; see below photo/link for “Scroll of the Hungry Ghosts” (Gaki Zōshi 餓鬼草紙)

Animals. Tiryagyoni-gati in Sanskrit. Chikushōdō 畜生道 in Japanese. The realm of animals and livestock is characterized by stupidity and servitude.

Asura. Asura-gati in Sanskrit. Ashuradō 阿修羅道 in Japanese. The realm of anger, jealousy, and constant war; the Asura (Ashura) are demigods, semi-blessed beings; they are powerful, fierce, and quarrelsome; like humans, they are partly good and partly evil. See Hachi Bushu (8 Legions) for details.

Humans. Manusya-gati in Sanskrit. Nindō 人道 in Japanese. The human realm: beings who are both good and evil; enlightenment is within their grasp, yet most are blinded and consumed by their desires.

Deva. Deva-gati in Sanskrit. Tendō 天道 in Japanese. The realm of heavenly beings filled with pleasure; the deva hold godlike powers; some reign over celestial kingdoms; most live in delightful happiness and splendor; they live for countless ages, but even the Deva belong to the world of suffering (samsara) -- for their powers blind them to the world of suffering and fill them with pride -- and thus even the Deva grow old and die; some say that because their pleasure is greatest, so too is their misery. See also the Tenbu page and Hachi Bushu (8 Legions) page.

Is it possible that the six (6) TV Series that were broadcast are symbolic of the journey through the six (6) realms?

There are additional realms for the beings that have already reached the light.

1. Sravaka arhats Jp: shoumon [声聞]. Sravaka means “listener,” which is for those who have reached the light by following the teachings of Buddha. Arhats are the ones who have reached Nirvana and are free from the cycle of birth and death (samsara).

2. Pratyeka buddhas Jp: engaku [縁覚]. “Pratyeka Buddhas” means “independent or solitary Buddha”. For the beings who reached the light through their own effort, without the guidance of a teacher or the teaching of a Buddha.

3. Bodhisattvas Jp: bosatsu [菩薩] Bodhisattvas are beings who have generated the wish to reach Buddhahood for the benefit of all sentient beings. They postpone their own final rise to the light to help others find liberation. *Jizō is the perfect example.

4. Buddha Jp: hotoke [仏] the term “Buddha” is for the beings who have reached the light, with full wakening, and possess complete wisdom and compassion. The term “Hotoke” is commonly used in Japan to speak of a Buddha.

*In “Shogun Assassin,” Lone Wolf names his son “Daigorō,” a Japanese mnemonic warning about the 5 states.

To give more details, the Japanese name Daigorō [大五郎] carries significant meanings that sprang from its kanji components. The name is most likely a male one, and is composed in two parts:

Dai [大] in one aspect can mean “Big” or “Large”, signifying greatness or importance.

Gorō [五郎] can be translated as “fifth son”. Go [五] means five (5), and Rō is a suffix often used in male names, meaning “son” or “young man.”

Thus, the name Daigorō can be translated as "big fifth son" or "large son," which mirrors a traditional naming convention in Japan where the order of birth is often part of the name.

Furthermore, there are variations of the name that comprise different Kanji, leading to alternate meanings:

Here, written using these characters for Daigorō [大悟郎], Go [悟] means “enlightenment,” leaning to a connotation of wisdom or understanding, while Rō [郎] keeps the meaning of son.

Written this way, Daigorō [大吾朗], Go [吾] can be translated as “myself”, while Rō [朗] means “bright” or “cheerful”.

***To be Updated ***

*********

Source

Weekly Manga Action

Futushaba

Shōnen Magazine

Shonen Magazine official

Japan Resell - Weekly Shōnen Magazine

Dark Horse Comic - Lone Wolf and Cub Omnibus Volume 1 TPB

Dark Horse Comic - Lone Wolf and Cub Omnibus Volume 2 TPB

Archived Interviews: Kazuo Koike - The Dark Horse Interview 3/3/06

Introducing the Lone Wolf and Cub movie series.

Lone Wolf and Cub (Where to start?)

Masters of Animanga - Kazuo Koike Interview

Wikia Live - New York Comic-Con - Masters of Animanga Panel

Kazuo Koike, Goseki Kojima- Kubikiri Asa (Samurai Executioner) MANGA REVIEW

LONE WOLF AND CUB: The Best First Manga To Read? (Plus an Edition Comparison)

LONE WOLF AND CUB: The Gallery Edition | Making a Masterpiece

Lone Wolf and Cub

Lone Wolf and Cub, vol. 5 : Vent noir, de Kazuo Koike et Goseki Kojima

TV Asahi

OTAKU - Lone Wolf and Cub (2002) - Season 1 Compilation | Classic Samurai Action

IMBD Shogun Assassin - Anecdotes

橋幸夫「子連れ狼」

橋幸夫「三途の川の乳母車」

Tankōbon

EBESCO - Lone Wolf and Cub

GZA - Liquid Swords

Kill Bill Vol 2: Daughter About Her Scene

Traditional Kyoto - O-Jizo-sama

Shakujo. Shorinji Kempo demonstrations techniques embu. Stick monks. 少林寺拳法. 武道少林寺拳法

SŪTRAS & TEXTS ABOUT JIZŌ

GENIUS/GZA - MUCH MUSIC RAP CITY 1995 INTERVIEW

Liquid Swords: The Story Behind A Classic

Wu-Tang's RZA Talks Favorite MCs, BLM, Politics And Kung Fu With MSNBC's Ari Melber

Wu-Tang’s RZA Breaks Down 10 Kung Fu Films He’s Sampled | Vanity Fair

Comments